A young writer with verve and moxie spends time in Mexico, confronting both its exotic and unseemly aspects as she learns about her heritage.

By Alex Espinoza, Los Angeles Times, August 10, 2008

IT BEGINS with a memory: A 6-year-old girl hurls herself in front of a moving car. Sustaining a badly split lip and nothing more, a young Stephanie Elizondo Griest decides that automobiles are best avoided altogether. The specter of children dashing across the asphalt, “perhaps images of my former self,” haunts her on those rare occasions when she does drive. So call it divine intervention or simple chance when Griest, en route to Corpus Christi, Texas, from Los Angeles, encounters a group of people, one a child, darting across a hot stretch of Interstate 10. It is a startling image — unnerving, crystalline, visceral — meant, it seems, exclusively for her on this isolated ribbon of highway. “My lifelong phantom has actualized,” she writes.

Prompted in part by that encounter, Griest determines she must venture south of the frontera to make peace with the elusive “Mexicana” inside of her, the side she tried so hard to eradicate as a child because of stigmas and preconceptions, only to embrace it as a young adult in order to reap its benefits. She confesses: “Nearly every accolade I have received . . . has been at least partly due to the genetic link I share with the people charging through the snake-infested brush.”

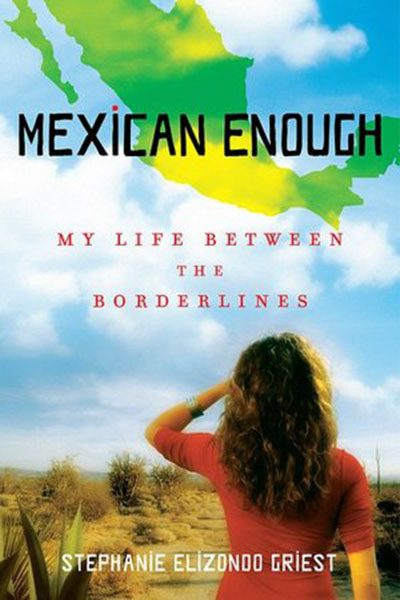

But if it is guilt made manifest on a lonely freeway that drives Griest to bid a temporary adios to her Brooklyn apartment and board a plane for Mexilandia, it is her steadfast and shrewd journalism that prevents “Mexican Enough: My Life Between the Borderlines” from becoming a puerile vision quest. Instead, it speaks with such ferocious and unyielding honesty that it is difficult to ignore this work.

Griest combs the country and encounters priests, gay rights activists, a half-Vietnamese dominatrix and workers returning home from the U.S. for the first time in years. She attends protests, a quinceañera and a baptism deep in Zapatista territory, all the while driven by an almost manic desire to figure out the common denominator bonding her to this nation and its people.

At first, everything is simple enough as Griest embarks on her pilgrimage. She moves into a house full of gay men in the ultraconservative state of Querétaro. Her roommates, who christen her “Fanni,” teach her the concept of being flojo (lazy) and take her dancing in Mexico City’s hip, glitzy Zona Rosa district. She attends a luchalibre match and interviews wrestlers with catchy monikers like Atómico and Dance Boy. She chases down the ghosts of dead ancestors in the dusty town of Cruillas in Tamaulipas.

Griest moves on to more serious concerns as the salsa music fades and the taste of too many aguas frescas wears off. Back in Querétaro, she investigates the death of Octavio Acuña, a gay activist who ran a shop selling condoms, adult novelties and safe-sex pamphlets — taboo subjects in a region where Catholicism is king. The facts surrounding Acuña’s death and the lackadaisical attitude the authorities display in investigating the crime are ominous and chilling. Just as unsettling are the statistics Griest supplies about the disappearances and killings of dissidents, like the 2001 murder of Sister Digna Ochoa, a well-known human rights attorney and activist.

In Oaxaca, Griest meets Claudia, a young Zapotec orphan being looked after by a boutique owner who is building an orphanage with money she makes catering to tourists. Claudia is charming and quick-witted, and she and Griest instantly bond. For a while, Griest considers adopting the child herself. She “envision[s] what this world would be like. Baking Christmas cookies. . . . placing a cool cloth on her forehead when she breaks a fever.” But is displacing Claudia from her own rich heritage the solution to the girl’s ills? Griest takes stock of her own situation and wonders whether stability and cultural solidarity trump opportunities only El Norte can provide.

Griest — author of “Around the Bloc: My Life in Moscow, Beijing, and Havana” and co-author of “100 Places Every Woman Should Go” — is at her best when she’s flexing her journalistic muscles, excavating information, assembling and supplying facts and statistics, and putting a human face on complex issues. At times the narrative slips into romantic daydreams and obsessions with relationships, more the stuff of a journal than journalism. Pat observations about the amount of Coca-Cola that Mexicans consume or their obsession with death and carnage add nothing new and serve only as distractions. There are also moments when physical descriptions echo those of a 19th century European ethnography, where a “flat Zapotec nose” and “Olmec faces” reduce the people to museum artifacts, oddly fascinating and exotic.

Nevertheless, through it all, one thing is undeniable about Griest: This chica ‘s got guts. The systematic self-incrimination she repeatedly displays and the frenzied compulsions fueling her quest to figure out just how Mexican she truly is — if at all — are what make Griest’s work important. It speaks to the larger truths all biethnic individuals are fixated on but aren’t always as willing to expose with such intense honesty and nerve. So we continue watching with an interest best described as uneasy. We know what is at stake for this writer, for all hyphenated Americans confronting their heritages, each curious to see what happens when Griest chooses to fling herself in front of the next moving vehicle, hoping the epiphany it heralds will be enough.

Alex Espinoza is the author of the novel “Still Water Saints” and teaches English and creative writing at Cal State Fresno.

* * * * *

Princetonian Enough: Writer Stephanie Elizondo Griest returns to the land of Bent Spoon ice cream and Small World Coffee to talk about Mexico

by Ilene Dube, Princeton Packet, October 4, 2008

CRAVING adventure in Mexico, but don’t have the cash, time, or just plain pluck to go? Then travel along with Stephanie Elizondo Griest in Mexican Enough: My Life Between the Borderlines (Washington Square Press, $14). Ms. Griest not only has the courage to embark on escapades most of us couldn’t dream up, but she writes about it in a lively, humorous way.

The former Hodder Fellow at Princeton University will return to the area Sept. 29 to satisfy her craving for Bent Spoon ice cream and Small World coffee, and give a book talk at the Princeton Public Library.

In her previous travel memoirs, Around the Bloc: My Life in Moscow, Beijing, and Havana (Villard Books Trade Paperback, 2004) and 100 Places Every Woman Should Go (Travelers’ Tales, $16.95), she took us along for the ride to numerous exotic locales. The first, named best travel book of 2004 by the National Association of Travel Journalists, follows the author on a tour through three communist and formerly communist cities.

We learn about her frustrations with telephones and all the other things that just don’t work, the challenges of buying a train ticket in a country where there are a dozen ways of saying “no,” doing laundry in a bucket, food shortages and mealy apples.

In one of the more memorable scenes, Ms. Griest witnesses a man collapse in a market in Russia. No one rushes to help him, despite her cries for help. Instead, an old babushka slaps him in the face and steals his sack of potatoes.

”Wanderlust pumps through my veins,” she wrote in the second book. “I’ve explored two dozen countries and all but four of the United States in the past decade, and ache for more.”

In fact, when interviewed for that book, she admitted to being sort of homeless in that she was constantly on the road, either touring to promote her books or on to the next book’s adventure. Writers residencies from Arkansas to Barcelona have provided a home base for the nomad.

A Corpus Christi, Texas, native, Ms. Griest is the daughter of an American father and a Mexican-American mother, whose great grandfather came to this country as a ranch worker. In fact, her mother is so Americanized (Mexicans are Americans too, of course, but she uses America here to refer to the U.S.), Ms. Griest went south of the border to learn more about her ancestral culture. She sought to improve what she refers to as her “Tarzan Lite” Spanish — a primitive vocabulary spoken entirely in the present tense.

”My mom faced so much ridicule for her accent growing up that she never taught my sister or me how to speak the language properly,” Ms. Griest writes.

The book chronicles her journey from the narco-infested border town of Nuevo Laredo to the highlands of Chiapas. She investigates the murder of a prominent gay activist, sneaks into prison to meet with resistance fighters, rallies with rebels in Oaxaca, and interviews undocumented workers and the families they left behind.

Despite these adventures, Ms. Griest is vulnerable, and has some of the same fears we armchair travelers do. For a South Texan, “Mexico means kidnappings and shoot-outs in broad daylight in Nuevo Laredo, or the unsolved murders of young women in Juarez,” she writes. “It means narco-traffickers in every cantina and explosive diarrhea from every comedor.”

So, at first, the thought of giving up her day job, putting all her possessions into storage, and using her meager savings for another adventure with an unknown ending was daunting. In the early part of her third decade in life, she was beginning to be uncomfortable about “sleeping (alone) on a futon in a cramped apartment with multiple roommates while my friends have wandered off, bought houses, married and procreated.”

Nevertheless, wanderlust is in her DNA, as she has said. “If I only spoke Spanish, I would be more Mexican.” She laments losing a large part of her history because she never understood the language of her abuelita, never heard her stories. “It pains me to think of the stories I missed from my grandparents,” she says from Corpus Christi, where she was helping her parents prepare for Hurricane Ike.

In an attempt to “Mexify” herself, Ms. Griest decorated her room with images of Frida Kahlo and the Virgen de Guadalupe, drank margaritas, and changed her middle name, Ann, to her mother’s maiden name, Elizondo.

But as soon as she landed in Mexico City International Airport, her luggage was lost, and the adventures take off from there. One of her new-found friends teaches her that in Mexico, “We have miracles.”

This past summer, Ms. Griest was renting a bungalow on the coast near Corpus Christi, before hitting the road again for her 22-city book tour. She and her new boyfriend had biked along the sea wall to see how the water had risen several feet.

”He’s my first real boyfriend,” she says. But there’s no danger of her settling down. “He travels even more than I do.” A plastic surgeon, his travels take him around the world to provide help for children with cleft palate. She may very well have found the perfect mate.

Her next book will be about silence, and therefore she is not talking about it, other than to say it will include her usual themes: social justice issues, human rights and women’s rights.

* * * * *

Found in Translation: Global wanderer Stephanie Elizondo Griest goes native in Mexican Enough

By O. Lani, San Antonio Current, October 1, 2008

Think back to a long, rugged road trip you’ve taken: the unexpected obstacles, the storytelling stragglers you met along the way, the inevitable heated argument sparked by a car breakdown. Add these elements to an impromptu journey of self-discovery and you’ve got Stephanie Elizondo Griest’s Mexican Enough: My Life Between the Borderlines.

This nonfiction collection by the Texan author of Around the Bloc maps out the author’s travels from one end of Mexico to the other, carefully detailing the festive traditions and historical moments that have shaped and molded modern-day Mexico and its people. Despite the ever-invading American influence of Wal-Mart/Sam’s and Coca-Cola, Elizondo Griest captures an enduring Mexicano sentiment and floods the senses with Mexico’s tranquil spirit.

The philosophy ni modo, or “oh well,” is explained by one of the many characters she comes to know: “We can either live tranquilo or we can worry about things we cannot change.” Elizondo Griest illustrates how this rings true on many levels in her description of towns full of women who are left behind by fathers, brothers, sons, and husbands seeking better lives across the Texas-Mexico border. She reminds us of the many who live openly gay lives among the outnumbering traditional Catholics, further uncovering the turmoil masked by the calm.

From the self-proclaimed flaming flojos of Querétaro to the pensionless Braceros of Aguascalientes, Elizondo Griest’s accounts of the angst-driven people of Mexico explores the reality of holding onto a treasured culture while also wanting desperately to be accepted by another. Though she is determined to be more in touch with her Mexicano self, another world of questions and traditions is unearthed before her.

A Corpus Christi native born to a Mexican-American mother and a Caucasian father from Kansas, Elizondo Griest vividly communicates why her search for a stronger sense of cultural identity within this tossed salad of a world is so important. Asked about nurturing her connection to her Mexico roots by developing her Spanish-language skills, she describes it in one word: Liberation. “Spanish was always the joke I was never in on, the party I was never invited to,” she said, “and maybe, I even sort of resented that because I was so frustrated I couldn’t speak it and had so many ridiculous hangups about it.”

Throughout her travels, it seems as though the author is trying to engage life’s larger struggle: being accepted as a good person despite cultural differences. About a quarter into her journey as both an outsider and a writer, she realizes that her ways and the ways of her hosts and companions are headed for a collision. Her initial lack of communication skills isn’t the only difference between her and the people she is faced with, and true acceptance by Mexico’s people was not to be achieved so quickly. In one instance, she is scolded by her housemate and dubbed fria while documenting tales of border crossings because her livelihood is based on the tragedies of others. Her housemate continues his condemnation by reprimanding her for not pitching in on household chores, implying that an American has invaded and expects to be waited on hand and foot.

This is just one of many episodes in which the author comes face to face with strongminded individuals. In another, she spends time getting to know socially conscious luchadores, Mexico’s famed masked wrestlers whose battles within the ring emulate the fight between Mexican citizens and their corrupt and negligent government for fair wages, better living conditions, and honest politicians. One luchador confesses: “Everybody likes to see a good fight, whether it’s between cocks, dogs, or us.”

Mexican Enough will escort you through a landscape of “magueys, lazy desert octopi with aquamarine leaves swirling in the wind,” and lead you down roads filled with “caterpillar eyebrowed little girls,” and meat-chopping toreros, bullfighters, with “wormlike scars burrowing from one end of the face to the other,” to the clandestine Zapatista Guerrillas of Chiapas and a minimum-wage-funded coming-out party for a 15-year-old that’s not to be missed.

Expect a turbulent tone fueled by a yo-yo linguistic style that swings from slang to pedantic rhetoric, a sign of the author’s own inner battle between what was taught to her and what she finds on her expedition. This makes for a shaky ride, but it emphasizes the underlying tale’s internal conflict. What resonates deeply is the author’s references to similarities among different cultures based on her world travels. “I felt really embarrassed that I didn’t know about Mexico the way I was supposed to,” said Griest. “I’m not supposed to know anything about Russia or China, but it’s so different with a culture that’s supposed to be your own. It was shameful for me.”

Her decision to focus on some events in detail while only cursorily describing others can be frustrating, such as her thorough description of the caste system within Mexico’s bus depots versus her very brief observation of pilgrims in Tepoztlán who are drawn to the energy vortex — something the reader may prefer to know about more than which class of bus offers refreshments. Yet, despite these shortcomings, Elizondo Griest is successful in reaffirming that we are more alike as human beings than we care to admit.

* * * * *

By Yvette Benavides, San Antonio Express News, August 17, 2008

Stephanie Elizondo Griest has been everywhere.

In “Around the Bloc: My Life in Moscow, Beijing and Havana,” Griest handily moves through communist bloc countries.

Griest traveled to most of the places she describes in her second book, “100 Places Every Woman Should Go.”

The 34-year-old writer who is, as she explained in a recent phone interview, “half Mexican,” recommends that readers travel to their Motherland. That’s the inspiration for her latest book “Mexican Enough: My Life Between the Borderlands.” She will be in San Antonio Tuesday to read from the new work and sign copies.

Griest has “polished Chinese propaganda” and “mingled with Russian Mafia,” but it was in Cuba where she realized that she couldn’t communicate with anyone.

“I kept thinking, if they could only speak Russian, I could talk to them,” she said.

Griest, who grew up in Corpus Christi, confesses she “had a really complicated relationship with my Mexican heritage. I actually did not grow up speaking Spanish because my mother had faced a lot of discrimination for having a Spanish accent and chose not to pass it on. And this is a reality I think for a lot of South Texans.”

During her world travels Griest was “constantly meeting these people that really had such a strong pride for their culture.”

She “stockpiled” language tapes and books to no avail. She had to immerse herself in her Motherland, just as she had prescribed to readers of her second book.

Her crash course in Spanish started in Mexico on the last day of 2004 in Querétaro, a historic city in the center of the country. It lasted eight months and took her to every corner of the country.

Griest’s memoir doesn’t just make a passing nod to the sanitized mercados of border towns or beach resorts. She goes to work with her roommates and explores the hearts of cities and villages. She resolutely travels to the places where people do more than “eat, pray and love,” to borrow the mantra of the Oprah Book Club fans of Elizabeth Gilbert’s travel tome.

Griest also travels to the places where people work, struggle and die. That’s how invested she becomes in Mexico.

It is the same single-minded focus that readers enjoyed in the award-winning “Around the Bloc” that makes us stay with Griest on the dusty, treacherous paths to San Cristóbal de las Casas or while she tries to prevent the destruction of the art installation of Malaleche (spoiled milk), a group of women who protest the government’s indifference to the murders of women in Ciudad Juárez.

Griest’s intense desire to discover her identity is at the heart of this thoughtful and thoroughly researched volume. To that circuitous end, she cites scholarship on everything from immigration and the contentious border wall issue to historical and sociological studies — she even footnotes a basic recipe for capirotada. The perceived “schizophrenia” that impels her is only part of the motivation on the road to discovering if she is “Mexican enough.”

Stephanie Elizondo Griest will read from her book and sign copies at 7 p.m. Tuesday at Borders at the Quarry.

Yvette Benavides is an associate professor of English at Our Lady of the Lake University.

* * * * *

‘First Stop in the New World’ by David Lida and ‘Mexican Enough’ by Stephanie Elizondo Griest: Fresh takes on an old country

Sunday, August 17, 2008

By EDWARD NAWOTKA / Special Contributor to The Dallas Morning News

You’ll be robbed, kidnapped and probably murdered; the traffic is at a constant 24-hour standstill; the air is so bad that breathing it is like smoking two packs of cigarettes a day; you can’t drink the water, the food will give you diarrhea …

Those aren’t slogans you’re likely to see on any travel poster for Mexico City. Yet, it’s what many Americans believe to be the truth: Mexico is just too dangerous to visit. Besides, isn’t all the best stuff Mexico has to offer readily available in San Antonio?

Journalists David Lida and Stephanie Elizondo Griest disagree. The authors of a pair of new books (First Stop in the New World and Mexican Enough, respectively) challenge many of these hoary old clichés.

Mr. Lida, a former New Yorker who has lived nearly 20 years in D.F. (short for Distrito Federal and a nickname for Mexico City), offers his services as an opinionated Virgil through its labyrinthine streets. Reflecting the “improvised, ad-hoc nature of life in Mexico City,” he caroms from the enthusiasm of the Chilangos (a mildly offensive slang term for residents of the capital) for the Virgin of Guadalupe to the Mexican national soccer team to the city’s poor urban planning and, yes, appalling traffic.

Mr. Lida’s method results in a mosaic of life in the city. Highlights of his book are his many brief portraits of the city’s cosmopolitan denizens, such as a Brazilian model, a would-be porn mogul and a hip Englishman who opens a Tiki bar.

In Mexican Enough, Stephanie Elizondo Griest describes how on Dec. 30, 2004, she, too, moved to Mexico, motivated by a need to resolve her conflicted feelings about her mixed ethnicity (her mother is Mexican, her father is from Kansas). A Corpus Christi native who rarely visited Mexico, Ms. Griest’s goal is to learn Spanish and “Mexicanize” herself.

The result is nearly two-year journey of self-discovery during which she befriends gay activists, seeks out Zapatista rebels in Chiapas and strikers in Oaxaca, and meets countless women abandoned by men who’ve emigrated to El Norte. She also tracks down ancestors in the town of Cruillas, a place reportedly wiped off the map when its residents were hired by Richard King in 1854 to work on the King Ranch in South Texas. (The story’s untrue. However desolate, the town remains.)

Where Mr. Lida’s and Ms. Griest’s books cross paths is illustrative of their differences: Both describe Aztec re-enactors in Mexico City’s Zocolo who offer ritual cleansing through incense. Mr. Lida is cynical about the promised limpia; Ms. Griest finds herself crouching down before them, “Breathing in the blue incense. Watching the Templo Mayor burst out of the pavement. Meditating history.”

Discussing Lucha Libre, the carnival-like Mexican form of professional wrestling, Mr. Lida interprets it using the theories of Nobel Prize-winner Octavio Paz; Ms. Griest interviews Bulldog Quintero, a half-deaf, gray-haired luchador who flips through his photo albums and reminisces about his 40-year career.

Where Mr. Lida is breezy, urbane and maintains a journalistic distance, Ms. Griest is earnest and full of wonder, befriending many of her subjects. Mr. Lida can sound like a spoiled urbanite when he bemoans the lack of jazz venues in Mexico City, while Ms. Griest’s exertions to cover the “big” issues (immigration, the oppression of the poor) occasionally feels dutiful. And while Mr. Lida’s agenda is sociological – he ultimately wants us to see Mexico as an example of a 21st-century hypercity – it becomes a personal paean. Ms. Griest starts on a personal mission but veers into sociological study.

The biggest difference ultimately lies in how the writers perceive themselves: Mr. Lida considers himself a Chilango; Ms. Griest acknowledges she will “never be Mexican, not even if I moved there for the rest of my life.”

Each view has its merits, and both books are insightful and entertaining. Read together, they offer a panoramic portrait of our beguiling neighbor, one that will have you dismissing those old, misleading platitudes.

Edward Nawotka is a freelance writer in Houston.

* * * * *

Mexican Enough: My Life Between the Borderlines

By Kelly Lemieux, Special to the Rocky Mountain News, Thursday, August 28, 2008

Book in a nutshell: Author Griest won a 2007 Social Justice Reporting award, partly as a result of traveling to Russia, China and Cuba, where she rubbed shoulders with both legit and illegit folks, reporting on both daily life and the injustices she found. For this book, the American Latina decided to explore her roots south of the border in Mexico, our troubled and exotic neighbor.

Mexican Enough is a warm mix of memoir and journalism as the author finds herself traveling from Mexico City to destinations north and south. It’s a sheep dip into Latin culture, a boisterous encounter with genuine people and their everyday concerns.

Highlights of the tour include the province of Chiapas, ruled by the ski-masked rebel Subcomandante Marcos; the narco-infested U.S./Mexican border, and La Joteria, the “Queer Palace” in Queretaro where Griest rooms with fabulously styled gay men whose clandestine network confounds Latin notions of machismo.

Best tidbit: One of the most painful stories in the book concerns Octavio Acuna, a gay activist found murdered after many incidents of police and community harassment, a disturbingly regular occurrence in Mexico. His lover, Martin, recounts Acuna’s dedication to a “Diversity Week” in college, AIDS prevention and safe-sex workshops.

Pros: Griest’s exuberant prose captures both the life-embracing passion of Mexican culture – parties, tequila and stormy relationships – and the Third World uncertainty of a nation divided by dirty-tricks politics and governmental subversion of democratic principles.

Cons: While the author attempts to elucidate the immigration debate that naturally arises when dealing with Mexico, her bias in favor of transnational personas clashes with an American nation grappling with dozens of identity-based political groups that might promote division.

* * * * *

Nonfiction review: ‘Mexican Enough’

By Elizabeth Fishel, San Francisco Chronicle, August 4, 2008

“What are you, Stephanie, Hispanic or White?” elementary school classmates would tease the young Griest in Corpus Christi, Texas, which is 150 miles from the Mexican border. Her father’s people came from the Kansas prairie and her mother’s from Mexico, so like many of our gumbo nation’s 7 million biracial citizens, including the presumptive Democratic nominee for president, Griest was pulled in both directions and ached to feel more comfortable in her skin. Mired in “an existential identity crisis,” she changed her middle name from Ann to Elizondo, her mother’s maiden name, and checked Hispanic on her college applications. In college she majored in Russian, then fled to China and made a four-year pilgrimage through communist countries because “her ancestral culture felt too intimidating.” From that 12-nation tour came her first memoir in 2004, “Around the Bloc: My Life in Moscow, Beijing, and Havana.”

Brooklyn-based, but highly peripatetic (note her second book, “100 Places Every Woman Should Go”), single and about to hit 30, she was a roots-saga waiting to be written. She headed across the U.S.-Mexico border in 2005, vowing to learn her mother’s tongue and explore her cultural heritage. But “history had other plans,” she writes, during that volatile year and a half that ended with the hotly contested Mexican presidential election. So her book about “the social movement that shook parts of the nation to the core” turned out to be more reportage than memoir. Gutsy, frank and likable, Griest has the journalist’s nose for the story rather than a memoirist’s inner eye for reflection and self-revelation.

If “Eat, Pray, Love” seduced readers to Italy for pasta-tasting or India for navel-gazing, “Mexican Enough” will not do the same for south-of-the-border tourism. Crisscrossing her mother’s homeland, Griest reports on the tense, charged, often violent side of Mexican culture. Gay-bashing and the murder of a young activist in conservative Queretaro. An Indian massacre by paramilitary in Acteal, Chiapas. The mysterious, disturbing kidnapping and slaughter of some 400 female manufacturing workers in the border town of Ciudad Juarez since 1993. Around every plaza, Griest sees evidence of Octavio Paz’s remark about the Mexican character and its “willingness to contemplate horror.” When she does an impromptu interview with a young gay man at a Mexico City cafe, he confides that he was just raped and robbed by street thugs. He then stuns her by adding that he “was so lucky” – he wasn’t killed.

Immigration is the beating heart of “Mexican Enough” because it is the core of her mother’s family’s saga and thus of the author’s. She writes eloquently that immigration “encapsulates the whole of human experience. Dreams, ambitions, envy. Struggle, sacrifice, risk. Culture clash and assimilation. Survival. Triumph. Death.” She listens to hundreds of border-crossing stories from the anxious wife of the “coyote” who escorts people to the United States for $1,000 a trip, risking his life each time, to the citizens of Aguascalientes, who return from work in the United States with low-riding jeans and drug addictions. But when her mother joins her hunt for family history in the dusty village of Cruillas, Griest misses a chance to take her quest deeper. Her journalist’s eye for detail stays sharp, but the emotional connection that makes a memoir memorable – reactions recorded, secrets shared, ambivalence probed – doesn’t materialize.

Just before Griest signs off, she makes a last-ditch effort to define her blended identity by doing an Internet search for the words “being biracial.” Seven traits come up – among them “feels more comfortable in racially mixed crowds; experiences identity crisis at some point in lifetime” – and this mix of qualities seems to be enough of an answer for now. “I just want you to find what you’re looking for,” her mother says to her earlier. It may take another book or two to pin that down from the inside out.

Elizabeth Fishel is the author of “Reunion: The Girls We Used to Be, the Women We Became.”

A chat with Stephanie Elizondo Griest (circa 2008)

1. You call yourself a “globe-trotting nomad” who has explored 30 countries and 47 of the United States. Tell us about your travels and how they have shaped you.

My great-great Uncle Jake was a hobo who saw America from the peepholes of boxcars, so wanderlust is encoded in my DNA! My travels began in 1996 in Moscow, where I mingled with the Russian Mafiya. (My boyfriend’s best friend was a freelance hit man.) Next stop was Beijing, where I spent a year polishing propaganda at the English mouthpiece of the Chinese Communist Party. Then I jetted off to Havana, where I belly danced with rumba queens. These adventures are the subject of my first memoir: Around the Bloc: My Life in Moscow, Beijing, and Havana.

While traveling in the Communist Bloc, I was struck by how fervently Stalin, Mao, and Castro tried to vanquish centuries of religion, tradition, and ritual by forcing their citizens to conform to socialist culture. Yet hundreds of thousands of people defied them. During the Soviet regime, East Europeans risked being banished to the Gulag by illegally distributing newspapers printed in their native language. Even today in China, Muslim Uighurs and Buddhist Tibetans gamble with imprisonment by worshipping in the officially atheist nation.

All of this made me reflect on how, in the United States, those of us who haven’t needed to fight for our culture have often deserted it. I, for instance, had invested little time or energy in learning about my Mexican heritage. I couldn’t even speak Spanish! So after traveling all over the world, I realized the need to turn inward.

2. But you grew up in Corpus Christi, Texas, just 150 miles from the Mexico border. Why didn’t you learn Spanish as a kid?

My mother faced so much ridicule for her Spanish accent growing up, she never spoke it at home. She wanted to spare my sister and me the humiliation of mispronouncing our ch ‘s and sh ‘s. There wasn’t much incentive to learn Spanish at school, either. Back then, “acting Mexican” was considered an insult in South Texas schoolyards. Moreover, I had a serious case of wanderlust. Spanish was the language of the place I wanted to leave. That’s why I majored in Russian in college and then studied Mandarin.

3. So how did you finally decide to move to Mexico in 2005?

After completing my road-trip/book tour for Around the Bloc in 2004, I had to drop off my rattle-trap car at my parent’s house in Texas. (I was living in Brooklyn at the time.) While driving down I-10 between Tucson and El Paso, I took what appeared to be a scenic farm road curving along the Mexican border and wound up deep in the desert. After about half an hour, it occurred to me that not one car – or anything else – had passed by on that desolate road. Moreover, my gas gage was nearly empty, my cell phone was out of range, and it was about 100 degrees outside. If my car broke down, I was toast. I was just about to turn around and rejoin the main highway when objects appeared in the distance, in the middle of the road. Moving sluggishly, then quickly. When I realized they were people – most likely Mexicans fleeing the border – I squeezed the brakes and blared the horn. My first thought was that they needed water, so I started slowing down, in order to offer them a bottle. But then my mind started racing. What if water wasn’t all they needed? What if they asked me to take them somewhere? Of course I would say yes. How could I deny a ride to people in the middle of the desert?

But…. what if they didn’t just want a lift? What if they wanted my car? Or what if they just took it? Tossed me into the cactus and roared away? That’s what I would be tempted to do, if the tables were turned: Throw out the gringa and go.

The irony of the situation was immediate. Nearly every accolade I had received in life – from minority-based scholarships to book contracts – was due in part to the genetic link I shared with those people frantically charging through the brush. What mainly distinguished us was a twist of geographical fate that birthed me on one side of the border and them on El Otro Lado. They were too Mexican; I was just enough. When I looked into the desert mountains from which they descended, I realized that it was time to go to Mexico. So I bought a plane ticket and flew out a few months later.

4. Your first stop was Querétaro, where you lived in a house full of gay men. Tell us about that. How do gays and lesbians fare in Mexico?

A Chicano artist friend of mine had been living in Querétaro for years, but was about to leave when I arrived. He offered me his space: a bedroom in a house shared by three Mexican artists, two of whom were gay. I moved in and discovered that my new home was the epicenter of the city’s gay community. Young gay men flocked in at all hours of the day and night. Since the majority lived with their parents (most of whom didn’t know they were gay), our house was their oasis. Upon crossing our threshold, they’d beeline for the bathroom, where they’d dip into the communal jar of gel and spike their hair into tufts. Then they’d blast Dead Can Dance, flip through fashion magazines, hold their boyfriend’s hand, tell stories. I loved it: not only were they entertaining, they taught me a far more colorful vocabulary than I was learning at the language school down the street! I lived there for four months, and it was like a seminar on Gay Mexico.

The gay rights movement is actually making strides there, especially in the capital. In 2006, Mexico City passed a same-sex civil union law that gave gay couples the right to inherit pensions and property, join health and life insurance policies, and make medical decisions for each other. The border state of Coahuila has since passed similar legislation. But even so, Mexico is a fervently Catholic nation led by clergy who aggressively campaign against alternative lifestyles. It is also infested with “macho” men who torment homosexuals. Nearly 300 Mexicans were murdered because of their sexual orientation between 1995-2003. In fact, the foremost gay activist in Querétaro – a 28-year-old clinical psychologist named Octavio Rubio Acuña – was assassinated in his condom shop just a few months after I moved away. I investigated his slaying, and nearly everyone I interviewed believed that the local police were responsible.

5. You befriended a number of undocumented Mexicans living in the United States and then visited their families back in Mexico. What do those families think of immigration? How has it impacted them?

It is pretty devastating, actually. One in ten Mexicans currently lives in the United States, and hundreds of thousands more migrate every year. The bulk do so by crossing the 2,000-mile border with a human smuggler, and at least 500 perish annually along the way. With one phone call, their families back in Mexico learn that they will never return. That they vanished in the desert. That they got arrested, no one knows why. So the United States seems like a black hole to these families. An abyss that sucks people away. They don’t know where their loved ones work, what they do, who they live with, who they cross with. They don’t know the name of their new hometown, which state it is in, or even what side of the country. They just pocket the paychecks they wire home every 15 days and wait for their return. Some don’t. Tightened security at the U.S. border has made it much more difficult, dangerous, and costly to cross. Rather than being deterred from entering, migrants who’ve already made it are staying for longer periods of time (if not permanently) to amortize the expense. This is the terrible irony of immigration: people go in order to help their families, but sometimes end up abandoning them.

6. Has NAFTA helped the situation at all? When it was passed in 1994, Mexico’s then-President Carlos Salinas declared that it would create jobs instead of migrants.

I hate to simplify such a complex trade agreement, but NAFTA has essentially brought great riches to the wealthy and further impoverished the poor. I met countless farmers who were able to support their families just fine – until NAFTA. The price of staples like corn and coffee have since been driven so low, it costs farmers more to grow than what they would earn selling. Many are now subsistence farmers, tending only what their family can eat and allowing the rest to go fallow. According to a 2003 Carnegie Endowment report, some 1.3 million Mexican farmers were forced to quit their fields within the first decade of NAFTA alone. The bulk migrated to the United States.

If the United States truly wants to curb the flow of immigration, it is imperative that NAFTA be amended. U.S. economic policies are actually a major reason why so many Mexicans migrate in the first place.

7. You traveled to Oaxaca at a momentous time. Tell us about it.

Oaxaca is a fiery state, and a populist rebellion has been fomenting there for years. But it shifted into high gear in May 2006, when tens of thousands of public school teachers from around the state descended upon the capital, erected tarps throughout the downtown area, unrolled their sleeping bags, and refused to budge until they got a pay raise. They had actually done this every summer for the past 26 years, but because 2006 was an election year, their strike lasted longer than usual. Not only did this threaten to leave a million students without a teacher once classes resumed, but it was an eyesore for tourists. So, in the predawn hours of June 14, Governor Ulises Ruiz dispatched 1,700 state police to clear out the teachers. You cannot underestimate the tenacity of a Mexican striker, however. The teachers defended their turf with sticks and stones, aided by activist groups who later formed a coalition called Asamblea Popular de los Pueblos de Oaxaca (Popular Assembly of the Peoples of Oaxaca, or APPO). The police fled town and APPO seized control of the city. I arrived two weeks later, and participated in a march of more than half a million people – or 20 percent of the state’s population. They resolved to continue striking until Governor Ruiz resigned. (He was fiercely unpopular even before the strikes, as he is widely believed to have stolen the election that landed him in office.)

APPO ruled Oaxaca until October 27, when plainclothes government agents battled protesters in a residential neighborhood and ended up killing five, including a U.S. journalist named Bradley Will. He filmed his own shooting, dying with his camera in his hands. President Fox responded by dispatching 4,500 Federal Preventative Police, an elite military force that arrested hundreds of protesters, including many innocent bystanders. Scores were beaten. The police took over the city and are still omnipresent today. Oaxaca is much calmer now, but flair-ups do occur. In June 2008, for instance, death squads killed two Mexican radio journalists.

8. You also sneaked into prison while in Oaxaca. What was that like?

Overwhelming. For starters, the prisoners weren’t inside their cells. When I walked in, a large group bum-rushed me, waving handicrafts in the air. None wore uniforms or handcuffs or even similar haircuts, so I initially thought they were vendors who somehow smuggled their goods inside. When I discovered they were inmates, every prison movie I’d ever seen flooded my brain. But Mexican prisons differ starkly from prisons in the United States. They only give their inmates enough food so they don’t starve and enough clothes so they aren’t naked. If they want to survive, they have to hustle.

The prison itself actually reminded me of a Chinese student dorm. Inmates sleep in bunk beds, six or eight to a room, and they can choose their cellmates. There seems to be few regulations about personal possessions: I saw crockpots, hot plates, cutlery, kitchen knives. I couldn’t help but contemplate how many different ways they could kill the guards, each other, or themselves – but apparently they don’t. They can also receive visitors inside their cells for three to four-hour intervals a day, and married couples can request private rooms for conjugal visits one weekend a month. Three of my cousins are currently imprisoned in the United States, and as far as I could tell, their Mexican counterparts enjoy a far more humane experience!

Mexico’s judicial system is another story, however. Human Rights Watch estimates that more than 40 percent of Mexico’s prison population hasn’t even been convicted of a crime. Torture-induced confessions are employed to solve about one-third of cases, and defendants are rarely granted much access to the judges who decide their fate. The justice system also tends to persecute the wrong people. In Mexico City, for instance, more than half of the 22,000 prisoners have committed crimes as heinous as stealing a loaf of bread. Politicians and businessmen who pilfer millions, meanwhile, either slip by unpunished or bribe their way to freedom. As the martyred Salvadoran Archbishop Oscar Romero once said: “The law is like a serpent. It bites the feet which have no shoes on.”

9. Did your year in Mexico make you “Mexican enough”? What does it mean to be “enough” of a culture, anyway?

It goes without saying that I will never be truly Mexican, not even if I moved there for the rest of my life and acquired the requisite customs and traditions. Because what binds a people are their bedtime stories. The songs they sing on road trips. Political and historical events. Fads and crazes. Shared memories. Not skills that can be acquired, like language. Which isn’t to suggest that my pursuit was a worthless endeavor. I am deeply proud that I can now speak the language of my ancestors. But I’ve learned the hard way that there is no point striving for an unobtainable state of being.

Identity crisis is actually endemic to the U. S. Latino community. I am a long-time member of Las Comadres, a national organization that networks Latinas from all nations. At practically every meeting, I encounter another caramel-skinned woman who speaks Spanish fluently, cooks arroz con pollo, and salsa dances on weekends, yet still doesn’t feel Latina enough. This is especially ironic considering that white society created what it means to be Latino in the first place. Colonists diluted indigenous blood through conquest and rape; the U. S. government drew up categories like “Hispanic,” “White,” “Black,” and “Other” and made us choose. Hollywood created the cholo while MTV gave us J. Lo. For generations, we’ve felt pressured to emulate these role models because they were our only ones.

But poco a poco, we are coming into our own as a people. We’re making strides in film, literature, non-profits, politics, science, music. Creating our own definitions of who we are and who we can aspire to be. Fulfilling the dreams of ancestors who struggled to root (or keep) us here. Striving to believe that – whatever we are – it is enough.

10. I was struck by the fact that you traveled alone throughout Mexico, and that your guidebook “100 Places Every Woman Should Go” strongly encourages women to do the same. Why?

Every woman should travel alone at least once in life, to better hear “Mother Road.” She is one of the most formative teachers around. She will push you to your physical, spiritual, and psychological limits – then nudge you one step further. She will teach you to be self-reliant and self-sufficient, which will allow you to stroll the world’s passageways with confidence. I personally have become such a self-sustained, self-contained unit, I’m expecting to self-pollinate any day now!

And I deeply encourage everyone out there to travel to their motherland at some point in life, to learn from the roots that grow within you. Even if you can’t find a living family member, you can ask around for the local historian (or oldest living resident) to see if they know your family name. Request relevant birth, marriage, or death certificates at the equivalent of the county clerk’s office; make rubbings of tombstones engraved with your family name at the local cemetery; fill a jar with earth. If nothing else, you’ll leave with the satisfaction that you witnessed the same sunset as your ancestors. That your boots collected the same dust.