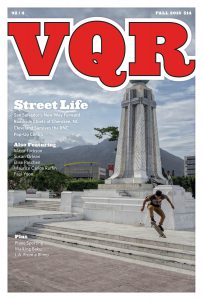

As more and more communities across the United States are (righteously) celebrating Indigenous People’s Day instead of Columbus Day, I thought it time to share my latest essay: “Chiefing in Cherokee: Commodifying a Culture to Save It,” which has been published in the Fall 2016 issue of the Virginia Quarterly Review. It examines the immense complexities of “chiefing,” or busking, in the Qualla Boundary, which is the ancestral home of the Eastern Band of the Cherokee Indian. What follows is the opening segment. My deepest gratitude to the many citizens of the Eastern Band who shared with me their perspectives on a wide range of difficult issues: identity, cultural appropriation, authenticity, privilege, and tourism. Thanks also to the photographer Stacy Kranitz for her powerful artwork (including the one accompanying this post, which is the lead photo in the VQR story).

CHIEFING IN CHEROKEE

By the time we rolled into Cherokee, North Carolina, Nick and I had been crisscrossing the country for three months straight, scouting for stories for an educational website called the Odyssey. Because it was the year 2000—that is, when cell phones were mostly used for urgent matters—we had filled our endless road hours with conversation. But neither of us said a word as we cruised down Tsali Boulevard, the town’s main strip. We just stared and shuddered.

Practically every storefront sign featured a Native American rendered in caricature above a business name like MIZ-CHIEF, SUNDANCER CRAFTS, or REDSKIN MOTEL. Store pillars had been carved and painted as totem poles. Teepees crested the rooftops. Souvenir shops advertised two-for-one dream catchers. Mannequins dressed in warbonnets waved from the windows. Nick and I had traveled here to research Andrew Jackson’s forced relocation, in 1836, of the Cherokee from their ancestral lands to territories out West. At least 4,000 Cherokee died from hunger and exposure along the way. We wanted to learn how the tribe had processed this tragedy, how they explained it to their children. Indigenous Disneyland wasn’t what we’d had in mind.

Up ahead, a billboard touted LIVE INDIAN DANCERS in a tawdry font. Nick pulled over so we could join a flock of tourists gathered around a teepee propped on the side of the road. Two men wearing elaborately feathered headdresses were midway through a performance. The younger one was playing a drum; the elder was telling a story about the Titanic. Too many people had crowded into the life raft, he said. They were sinking. Three brave men needed to make the ultimate sacrifice. A French man shouted, “Vive la France!” and jumped overboard. Then a Brit yelled, “Long live the Queen!” and jumped overboard. Finally, a Cherokee stood up. He looked around at all of the passengers and said, “Remember the Trail of Tears!” Then he grabbed a white boy and threw him overboard.

I laughed. The white tourists did, too. Nick, an Oglala Lakota Sioux from the Pine Ridge Nation in South Dakota, did not, which altered how I might otherwise have reacted to the next joke, and the one after that. Again and again the storyteller mocked his audience, and again and again they chuckled on cue. I didn’t know what to make of this. Were these jokes undermining the significance of the tribe’s calamities or intensifying them? And was laughing a sign of our complicity, or was it a strange way of seeking karmic forgiveness for the atrocities that some of our ancestors had committed against theirs?

No time to contemplate: Live Indian Dancing had begun. The storyteller took over the drum and started chanting while his younger partner stepped into the center of the circle of listeners. He wore regalia—war paint, dozens of beaded necklaces, a headdress and bustle made of turkey feathers—over faded Levi’s and sneakers. For about a minute, he shuffled his feet and bobbed his bustle as the tourists took pictures. When he bowed, the storyteller passed around a basket, which the audience filled with bills and coins.

I had witnessed touristic practices ranging from the questionable to the degrading the world over, but this struck me as something dangerously complex. Self-exploitation? I turned to Nick for guidance, as he was my de facto barometer for what was morally acceptable in Native America. He clenched his jaw in anger.

When the last tourist departed, we marched over to the performers. Though just nineteen years old, Nick had inherited formidable oratorical skills from his grandfather (who provided legal counsel for the American Indian Movement) and mother (who won the 1993 Goldman Environmental Prize), so he did our talking. One by one, he ticked off every instance of cultural misappropriation we had encountered there: how, historically, the Cherokee had never lived in teepees, raised totem poles, or performed the Sun Dance, and how they had certainly never worn that style of headdress. What gave these men the right to profit from traditions not their own?

The storyteller shook his tip basket. He fed his kids with this money, he said. White people, they didn’t know anything about Indians. He was educating them.

“How are you doing that? You are totally misrepresenting your history.”

He looked Nick in the eye. “You say you’re Lakota, eh? Do you speak the language? Do you know the dances and the ceremonies? I do. But I don’t do them here. They’re too sacred.”

And just like that, our righteous indignation fizzled. No, Nick did not speak Lakota—for the same reason that I, a Chicana from South Texas, did not speak Spanish. Our elders had suffered so much discrimination for using their mother tongues that they’d declined to pass them on to us. Although Nick and I had been hired by the Odyssey to represent our communities, we couldn’t actually talk with many of our elders. What, then, gave us the right to question these men? They knew their culture, which was more than we could say about our own.

Sensing that he’d hit a nerve, the storyteller invited Nick to sit with him, then picked up a drum and started singing. After a while, Nick joined in. They sang song after song together, until the next flock of tourists arrived. When the storyteller rose from the bench to open a new show, we slinked away.

In the year that followed, I drove more than 45,000 miles across the United States with Nick and other colleagues. Nothing affected me like that Cherokee trip. From that day forward, whenever I began another essay about Chicanidad, or wore a rebozo to a reading, I thought of those buskers dancing for tourists on the side of the street. Was I also commoditizing my culture when I performed my identity, or was I offering reverence to my ancestors? Could anything profitable be authentic? Did any of this matter if you were simply trying to survive?

For the full story, monitor VQR Online.